As must be incredibly obvious to anyone who followed this blog in the past, since starting my second blogging venture, Ultimate Bridesmaid, this one has had to take a back seat. The truth of the matter is I just can’t keep up with two regular blogs—in addition to working a full-time job, freelancing and having a life. That said, I’m still reading like crazy and people still ask me for book recommendations. So, I thought it might be fun and helpful to compile a list of the books I’ve read this year with a little mini review for you. It’s not nearly as robust as my previous posting, but it’s something.

A word about my star rating system. It’s on a five-star scale, but I liked anything I rate 3, 4 or 5.

Five: My ultimate favorites

Four: Great books that I loved, with strong writing, but just missing that “wow” factor of a 5-star rating

Three: Solid books that I enjoyed, but a few flaws jump out at me and keep it from being “great.” Also used for books by authors I love that disappoint me.

Two: A book that suffers from a lot of flaws, but had at least one interesting thing (usually the premise) to redeem it. Also books that were just “not for me”

One: Bad. Just bad.

1. The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt

Contemporary Fiction + Drugs + Art Theft + Coming of Age

5 stars One of my favorite books of the year. Tartt is a true contemporary master. At age 13, Theo survives a terrifying attack near his New York home—his mother does not. Young Theo finds himself passed along between a number of friends and relatives, from a luxury apartment on the Upper East Side to the suburbs of Las Vegas and back again. It’s a long and winding story, but so engrossing and what really sticks with you is the character development. Our antihero Theo is so utterly messed up, but you can’t stop watching him.

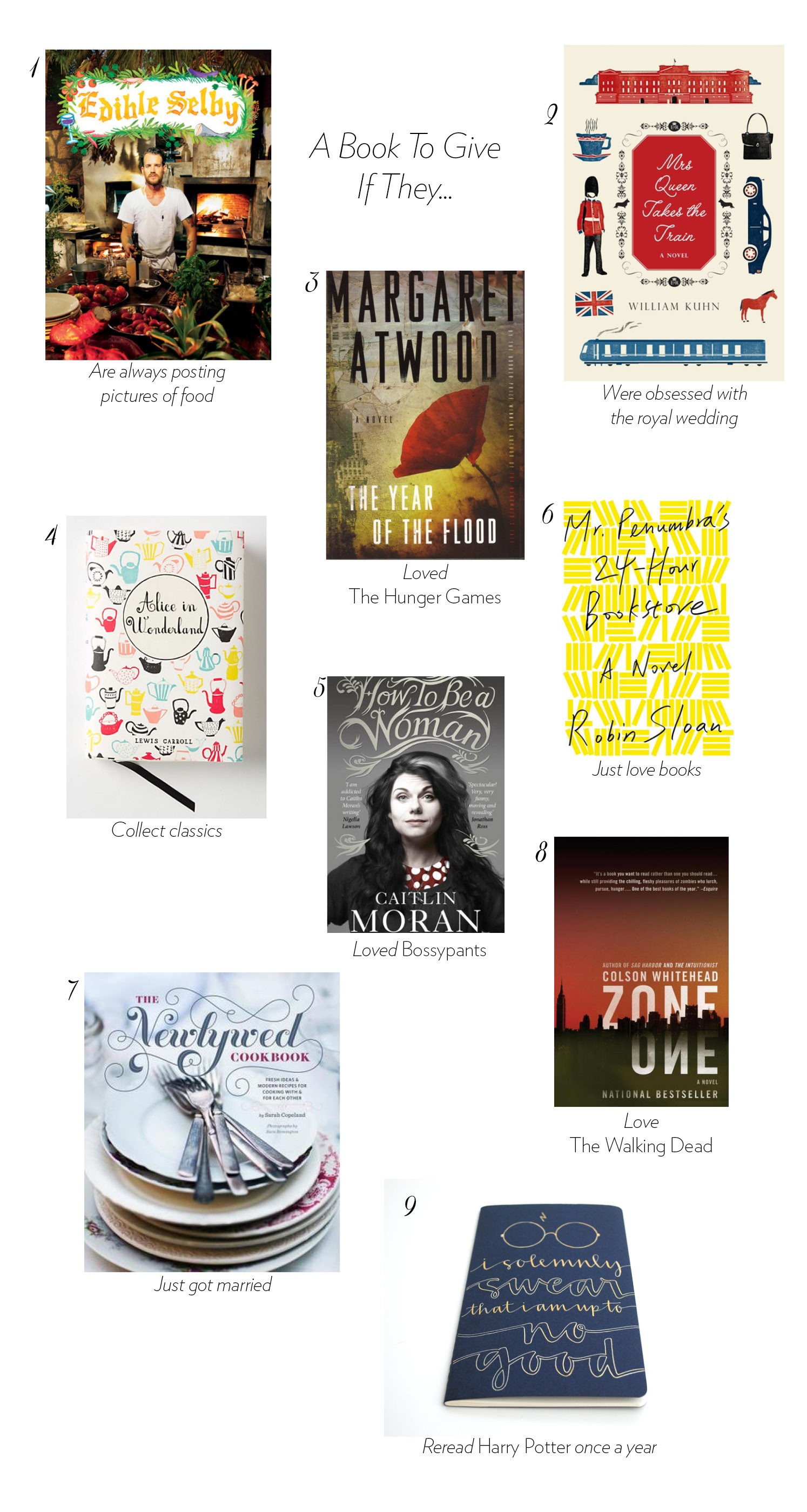

2. Mrs. Queen Takes the Train by William Kuhn

Contemporary Fiction + British Royals

4 stars I’m not sure what the Queen would think of this book, but I quite liked it. It asks the question, “What if the Queen was feeling a bit down and wanted to go on a little trip for the day to cheer herself up?” Unintentionally disguised in a skull-and-crossbones hoodie, the Queen takes the train, asks a few of her subjects about herself and scares the wits out of those charged with watching over her.

3. The Stockholm Octavo by Karen Engelmann

Historical Fiction, Sweden 1791 + Tarot

2 stars I was drawn in by the premise of this one, since I have something of an outsider’s interest in tarot, but the execution of The Stockholm Octavo really let me down. The pacing was all off, either painfully slow or skipping about, and the main character is flat, a sort of cipher through which the author explores Swedish political intrigue. My biggest pet peeve though: the main character is dumb, taking ages to realize things the reader knows at once.

4. The Perfume Collector by Kathleen Tessaro

Historical Fiction, Paris 1955 + Perfume

3 stars British housewife Grace travels to Paris when she learns she is the sole beneficiary of a mysterious perfumer’s will. This is a great airplane read—light enough that it’s easy reading, but with enough substance to keep you guessing. I liked the perfume angle and even learned a bit.

5. The Impossible Lives of Greta Wells by Andrew Sean Greer

Time Traveling + New York + Gender Roles

4 stars An excellent entry in what must be becoming a popular new subgenre: time travel or reincarnation fiction. In this case, after the loss of her brother Felix, Greta undergoes a radical shock therapy treatment that catapults her back into time, into the body of another Greta living in 1918 and then 1941. The three Gretas cycle through time as the treatment progresses, each looking for something in the lives of their doppelgängers that they’ve lost in their own time.

6. Where’d You Go, Bernadette by Maria Semple

Contemporary Fiction + Letter Format + Childhood Lost + Antarctica

5 stars Loved this one. One of my top recommendations from the year. It’s quirky, surprising, engrossing, engaging. 15-year-old Bee collects evidence in the form of letters, emails and newspaper clippings in an attempt to find her eccentric and brilliant mother, Bernadette, who has inexplicably disappeared days before a family trip to Antarctica.

7. Burial Rites by Hannah Kent

Historical Fiction, Iceland 1829 + Female Murderer

4 stars Agnes is sentenced to die for the murder of her master. But since prisons are nonexistent in this remote part of Iceland, she’s sent to a croft as a captive to work off her debt to society until her execution can be carried out. I enjoyed this historical fiction’s unique setting, especially since I’ve been to Iceland myself.

8. The Death of Vishnu by Manil Suri

Contemporary Fiction, India + Class Struggle

4 stars A bit of a departure from my usual, but this was an engrossing book that surprised me. Vishnu lies dying on the stairs of the Bombay apartment building where he serves as the errand runner. In something of a pre-death trance, he hears and experiences the family squabbles and class struggles of the inhabitants of the building, from the teenagers of warring families planning to elope to the man who comes to believe Vishnu is an incarnation of the deity whose name he shares.

9. The Orchardist by Amanda Coplin

Historical Fiction, American West + Orphans

4 stars Talmadge has been something of a loner since the disappearance of his sister many years ago, spending his days tending the family’s orchard in California. But when two orphan girls arrive on his property in need of help, Talmadge finds himself opening up for the first time, with life-changing consequences. A touching and beautifully written historical fiction.

10. The Complete Sherlock Holmes by Arthur Conan Doyle

Classic + Mystery + England

4 stars Yep, I seriously read every Sherlock Holmes story this year. Since I’m addicted to the BBC television version, I became interested in finding out how closely those stories related to the original, especially in terms of tone. My curiosity was not disappointed.

11. The Interestings by Meg Wolitzer

Contemporary Fiction + Coming of Age + Summer Camp + New York

5 stars My Mom recommended this book to me since I’m a former camp counselor because it centers on a group of kids who forms a tight bond at a summer camp for the arts. But while the camp angle drew me in, it’s what comes afterward that’s really interesting. Anyone can relate to this story about how we try to maintain childhood friendships even as our lives (sometimes radically) diverge.

12. Life After Life by Kate Atkinson

Historical Fiction, England 1910 + Time Traveling + World War I

5 stars My second trek into multiple lives/time travel, this is one of my top picks for the year. It’s just so devastatingly sad and incredibly well written. Ursula is born during a terrible snowstorm and doesn’t survive more than a few minutes. And then, after a brief period of darkness, Ursula is born during a terrible snowstorm and does survive at the timely intervention of the housekeeper. We watch as Ursula lives life after life, slowly moving toward some terrible imperative, some future she must finally make her way to.

13. The Golem and the Jinni by Helene Wecker

Historical Fiction, New York 1899 + Mythology

4 stars Really enjoyed this one. I do love a good mythological creature and this one gave me two I hadn’t often encountered before. A golem and a jinni find themselves alone and free in turn-of-the-century New York. The golem, a woman created from clay to serve a master, finds herself suddenly without one and at loose ends. The jinni, freed from millennia of imprisonment, struggles to find his place away from his desert home and remember how and why his captivity came to pass.

14. The Yiddish Policemen’s Union by Michael Chabon

Alternate History + Crime Noir + Judaism + Alaska

4 stars In this alternate history, the U.S. created a safe haven for Jews during World War II, allowing thousands to flee to Alaska and thus save themselves from the Holocaust. Sitka has since operated as a semi-independent Jewish state, but the land lease has almost ended and an entire city of people finds themselves on the cusp of homelessness. Detective Meyer Landsman has other concerns though—namely a series of murders that may be traced to the most religious and secretive sect of their society. Chabon’s story is intriguing, fast-paced and unique—and even taught me a few new Yiddish words!

15. The Storied Life of A.J. Fikry by Gabrielle Zevin

Contemporary Fiction + Books About Books + An Orphan

3 stars Books about booksellers or authors or bookstore owners can sometimes get on my nerves. I can easily get the feeling that the author thinks they’re being quite clever, but really they’re writing about the most obvious topic possible: writing. This entry in the genre manages to take a fresh twist with the addition of a plucky little orphan abandoned in an independent bookstore and raised by its curmudgeon owner.

16. The Bone Clocks by David Mitchell

Contemporary Fiction + Fantasy and Doomsday Subplots

5 stars Oh David Mitchell, you are so weird and wonderful. Will you never cease to try to surprise us? Only you could find a way to make a millennia-long war between two time-controlling secret societies a subplot. Just a blip in the narrative (well, more than a blip, but still). If you loved Cloud Atlas, this will be even more satisfying as Mitchell creates more links between each section, piecing together one complex tale through the eyes of many narrators.

17. Beautiful Ruins by Jess Walter

Historical Fiction, Italy 1962 + Contemporary Fiction, Hollywood

3 stars In 1962, an Italian innkeeper meets a film starlette who’s come to his remote hotel in a bit of trouble and he never forgets his encounter. Years later, he travels to Hollywood to track her down, with the help of the once-powerful director who is looking for his next big sell. This was a lovely, personal story and the author has a beautiful writing style. It gets bumped down to 3 stars because of the formatting, which distractingly jumps all over the place in terms of time period and narrator.

18. Indexing by Seanan McGuire

Mystery + Fairy Tales

3 stars A team of fairy tale police, including a Snow White, an evil stepsister, a Pied Piper and a shoemaking elf, investigate fairy tale crimes. The book was originally published as a digital serial so when you read the chapters all together there is a bit of an episodic feeling that keeps you from getting totally immersed in it. Each new chapter kind of fills you in on what happened “last time,” which makes sense for a periodical release but not when it’s all bound together as a novel. Still, I found this fun. If you like Jaspe Fforde, this is a lite version.

19. Love and Lament by John Milliken Thompson

Historical Fiction, North Carolina 1871 + Family

3 stars A solid historical fiction and not unenjoyable, but three stars as it also wasn’t particularly exciting or noteworthy. The story focuses on the youngest daughter in a family of nine and the many misfortunes that befall her kin. The writer is good at character studies, but the plot is slow. If you like this time period, give it a go.

20. The Ghost Bride by Yangsze Choo

Historical Fiction, Malaysia + The Afterlife

2 stars This was meh. I was drawn in by the concept, but the execution just didn’t deliver for me. The book was billed as being about a “ghost bride,” a living woman who is married to a dead man. However—spoiler alert—the woman in question never actually becomes a ghost bride though she does have some underworld adventures. My biggest pet peeve was that the main character is one of those who constantly does exactly the thing she shouldn’t do, for no particular reason, or assumes the exact opposite of the truth, again, just because. Don’t be so stupid, main character!

21. Dreams of Gods & Monsters by Laini Taylor

YA Fantasy + Angels and Demons + The Next Cult Addiction

4 stars Did you like The Hunger Games? Divergent? Are you shamelessly addicted to YA fantasy novels? Look no further for your next addiction. But you’ll have to start with Daughter of Smoke and Bone, the first book in this series. This year I read the third and final book in the trilogy and it did not disappoint (unlike some YA series I’ve heard of…). The plot is inventive and feels fresh and the writing clicks along, making this the kind of book you stay up until 3am reading because you just have to know what happens.

22. The Casual Vacancy by J. K. Rowling

Small Town English Life + We’re Not At Hogwarts Anymore, Kids

4 stars I finally got around to reading J. K. Rowling’s adult debut and let me start by saying this: if you expect it to be anything like Harry Potter, you will be severely disappointed. This tale is set firmly in the real world, following the struggles of a small town in the English countryside. Be warned, this book is heavy—there’s child abuse, rape, drug abuse, and even death in these pages—but Rowling does confirm herself to be a master of character writing. She has a way of really bringing people onto the page fully formed.